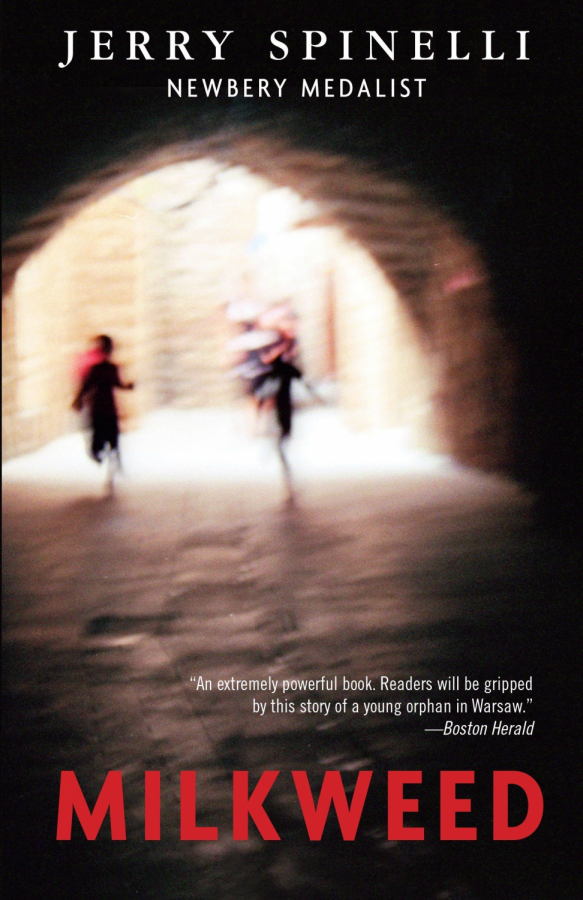

Milkweed Alternate Ending

May 7, 2021

Did you really dislike the ending to the novel “Milkweed” by Jerry Spinelli? Then read this alternate ending by seventh-grader Anya Read.

All I could feel was a sharp pain in my ear and pieces of gravel digging into my cheek, dripping blood on the rocky ground. I rolled over onto my back feeling relief that the pokey rocks were no longer hurting my skin. The sound of tree branches rustling and leaves hitting the pavement almost seemed like a ringing sound in my ears. “My ear!” I cried, quickly sitting up to touch the missing earlobe of my right ear to find that there was only a dried bloody stump. When I drew my shaky hands away from my stump, I could see disgusting yellow pus on my palms.

“What did you do to your ear?” I turned my head sharply to see Janina standing next to me, her hands on her hips looking sassy as ever. Her dress and face were covered in dirt. She was missing one of her once shiny shoes. Her other shoe wasn’t faring too well, the strap was falling off and the sole somehow disappeared. The shoe is still here, Janina is still here, I thought.

“Uri tried to kill me but he missed,” I stated bluntly as Janina kicked large rocks towards a broken-down building. She gave a little nod of understanding before speaking.

“Misha, we’re going to go find Tata, okay?” Janina demanded as she pulled me up roughly with her small hands, pulling me toward the train tracks. I tripped over my own feet and yelped. I tried to pry her hands away but she held on like an animal trap. Doesn’t She understand? Tata is gone! I was right but Tata didn’t listen, I thought while tugging on her hair, making her fall over. She tripped over and landed on the train tracks looking confused. “Don’t you get it? Tata is gone, the trains are gone, stupid girl!” I yelled at her. She bounced back up and smacked me before screaming back, “ He’s not gone, you’re lying!”

“You should listen to your brother, little girl. He’s right. Your Tata isn’t coming back. No one has ever come back.” a voice boomed from behind a bush. A man stepped out. He was wearing a pair of overalls and a white tunic covered in grim. His white hair blew in the wind as he leaned on a stick of wood that was shaped like a cane. “Are you Jews?” He asked quietly.

“Yes, I’m a filthy son of Abraham!” I exclaimed proudly pointing at my armband. The old man shook his head sadly.

“Come with me children, let me help you,” he blurted out quickly. Janina stared at me for a brief moment before intertwining our fingers, pulling me towards the man.

“I’m Janina and this is Misha, my stupid, smuggling brother.” She mumbled looking down at the ground. The man sank down to his knees to meet her eye level. She raised her head to stare at him stubbornly.

“My name is Luis. Why don’t you kids come with me and we can get something to eat?” He asked softly. Janina looked to me for approval. I nodded my head and followed Luis.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Luis was like a father to us, he showed us many things. How to cook, how to read, he even taught us to speak English. He took Janina and me to ride a carousel, like the one I saw in Warsaw years ago. He helped raise money for us to take a steamboat to America when I turned 18. I moved to Oregon and found myself working as an artist in a small shop in Garibaldi City. I met my beautiful wife, Esme. She sold flowers at the shop next door, her black hair was always tied up in a bun and her green eyes sparkled when she laughed. She inspired me to paint about the ghetto, Uri, and Mr. Milgrom. We got married on the 7th of June, five years later. We had two beautiful daughters, Anja and Tina, who grew up to become amazing women. Esme passed away three years ago, and ever since, I looked for the beauty in everything, sad things like rain, or graveyards to bright things like my grandson Uri’s smile.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

One Month Ago (2019):

Tina’s head leaned against the open window ledge of the diner. The cool sea air blowing in from across the shore, tossing her long black hair around the table, fanning it out like a darkened halo. Anja sat across from her sister drinking a cappuccino, her emerald eyes glaring into her cup as her grip on the fragile object tightened. She seemed troubled. I shifted one of my wrinkled hands away from my book and onto her hands, pulling the cup down. She reminded me of Tata, kind and generous yet strict. I opened my mouth to ask her what was the matter before I was interrupted by the bells and chimes of the diner door opening. A gust of wind blew the door all the way open, hitting the pole behind it. Screams of my grandchildren splashing in the ocean could be heard from the beach across the street.

“Mama, please let me help you,” Matthew’s voice boomed throughout the noise of the diner, followed by the retort, “Fine Matt, demean me as an old lady in front of all these people.” Janina’s voice dripped with sarcasm. The arguing couple made their way to our table. For the first time in almost a year, I laid eyes on my sister, still looking as beautiful as the day I met her. Her curly brown locks were now short and greyed but her hazel eyes still shined. My nephew Matthew stood behind her, rubbing his head, the mess of blonde locks that he called hair fell onto his face.

“I’ll leave you two to catch up. Better check on the little rascals at the beach anyway, I just hope they haven’t found the campfire lighter yet.” He bellowed, patting his mother’s shoulder before reaching around the booth to seize Anja’s wrist, pulling her with him. Anja snorted with laughter and grabbed her purse before walking out of the diner with Matthew, the door slamming with a loud bang behind them. Tina’s sleeping form was still curled into the corner of the booth.

Janina sat down slowly, putting her walker near the end of the table.

“How have you been, big brother?” She asked, smirking, just like she used to. I gave a half-hearted laugh. It’s been a while since we’ve been together like this. “Living one day at a time, sister.” Janina rested her head on her arm watching the children jump on Matthew, pulling him into the water while Anja was laughing. “I’m glad that they’re so happy, no child should have to go through what we went through,” She muttered at last. I fiddled with my fingers and stared at my feet. “Have you ever talked about the ghetto?” I looked up after she spoke. She was still staring out the window, watching a seagull go by.

“No, I haven’t,” I admitted. She gave a quick nod before the door burst open by screaming kids. Uri rushed in first, his red hair stuck to his forehead with seawater. He reminded me so much of the man he was named after. He even shared the same fiery red hair and the love for pickles.

“Babcia!” He screamed, throwing himself into her arms and holding on to her tightly. Janina wrapped her arms around him despite his soaking wet clothing. Clementine and Coraline walked behind him. Clementine’s lip was trembling, and Coraline was rubbing her eyes.

“Mama!” Coraline pouted. Tina lifted her head up from the ledge and grumbled. I stood up to let her out of the booth. “Uri got sand in our hair and Aunty and Uncle went to go get ice cream without us!” Coraline exclaimed, putting her hands on her hips just like Janina. Uri gave us a devilish smile and quickly sprinted to the jukebox to change the music. Tina picked up the twins, speed walking to the bathroom. Janina giggled, taking a sip of Anja’s cappuccino before making a sour face and spitting it out into a napkin. Our family sat talking for a couple of hours while people trailed in and out of the dinner, the sun starting to set, creating a peaceful atmosphere in the tiny restaurant. Janina and I said our goodbyes before walking out to our cars together. Clementine was guiding the way through the darkness with a glow stick, skipping up and down. Coraline had fallen asleep on Tina’s shoulder and was now sleeping comfortably in the back of her mother’s car. Anja and Uri waved to us before pulling out of the diner’s parking lot. I helped Janina into her white jeep which Matthew was waiting for her in.

“Remember what we were talking about, Misha. You should start speaking about the ghetto. It’s important for people to hear our stories,” She advised.

“I know sister, I will,” I whispered before walking to Tina’s car to think about what Janina had said. It wasn’t such a bad idea after all.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Present: 2020

I took a deep breath before walking out on the stage. I saw the flash of reporters and cameramen. My painting was framed on the wall. The piece of art had always been a bit eerie to me. The people frozen in time. Never blinking, never moving. I stared at the podium in front of me before speaking. “I’ve had many names in my life. Dziadek, father, brother, Oliver, Misha Piłsudski, Misha Milgrom, Stoptheif. These names have helped me thrive and survive. Without them, I would still be in the ghetto, buried in the ground. I dedicated this piece of artwork to the survivors of the Holocaust and the deceased.” I closed my eyes for just a moment before continuing. I thought about everyone I met while speaking. Mr. Milgrom, Mrs. Milgrom, Uncle Shepsel, Doctor Korczak, the orphans, all the other boys. Most importantly, Uri and Janina will forever be in my heart.

Alex Wassel • May 21, 2021 at 8:22 am

This was an amazing ending, i loved it!